Photo by Lucas Ihlein

By Laura Fisher

In November 2021 members of KSCA staged our second Land Studio camp in the Capertee Valley. We somehow skirted the covid cloud, which felt like surreal good fortune. The camp was yet again interlinked with the Uni of Wollongong course ‘Art, Nature and the Environment’, this time taught by KSCA’s Kim Williams. Sadly, only a few students were able to join us due to covid vaccination constraints, so we invited a range of other people to join us, including 4 valiant students from last year’s camp. We set up at Snowgoose Farm, thanks again to the hospitality of Emily and Stuart Dawson. Peter Swain welcomed us to Wiradjuri country and hailed the custodial lands we came from in his uniquely inclusive style, inviting us to reflect on art, generational change and the future we want to create.

Photos by Brogan Bunt

An on-and-off drizzle kept us cool, flattened our hair and somehow made things very vibrant. Cheerfully coloured rain jackets, ponchos and marquees expressed our collective good humour. Our composting toilets were yet again installed about the camp site and newbies initiated to the wonders of the system. More on that later.

Photos by Charlotte Moussa, Louise Duff, Lucas Ihlein and Erika Watson

Ditching the tent for mere swag and drizabone was Joe Skuse, a landscape planner with The Mulloon Institute. Joe had a big part to play on our first day, when we joined a number of members of Capertee Valley Landcare at Bimbimbie Farm, the property of Alex Bogle and Charlie Bogle. Alex is a new farmer in the Valley who has embraced regenerative principles, and she is also an expert beekeeper and curator - we were lucky to have such an enthusiastic host. Alex and Charlie have fenced off a degraded site on their property for restoration. It consists of two dams which they wish to return to a more natural state. Up the slope from the dams there is an erosion gully, and a number of areas of bare earth likely caused by overgrazing in the past.

Photo by Alex Wisser

Alex Bogle and Capertee Valley Landcare’s Kerrie Cook discuss the plan a few weeks before the camp. Photos by Laura Fisher

At Bimbimbie we did two things: an artistic adaptation of Landscape Function Analysis, and a brush packs project. Grounded in the science of ecosystem monitoring and restoration Landscape Function Analysis (LFA) is a method of getting intimate with a piece of ground - marked with a ‘transect’ - to assess its health. As Joe explained, it uses a range of indicators to determine whether that piece of ground is ‘aggrading’ (catching and building fertility) or ‘degrading’ (losing fertility). When done formally, it can be repeated every year or so to track change.

We wanted to offer people a taste of this exercise, and gave it a twist. We matched groups to transects located in different spots around the dams, and provided them with a large piece of cartridge paper with the transect market. We invited them to illustrate the page with the features they could identify on either side of the transect, and to puzzle over the how and the why. The activity inspired many thoughtful conversations about the signs of a healthy and unhealthy landscape, the direction of water flows, and why a particular area might be collecting nutrients or losing them. Joe encouraged us to transfer some of our insights to larger and larger scales of landscape change.

Photos by Alex Wisser

After lunch a fun-filled brush packs working bee began. We were aiming to kickstart the rehabilitation of the eroded areas of ground, and demonstrate a really simple method of ecosystem restoration. Brush packs are large piles of harvested vegetation perpendicular to the slope, constructed with a bit of care to be interwoven and weighty so they won’t be washed or blown away. As Joe explained, the beauty of the brush pack is that all you need are natural resources freely available on the farm, and some energetic humans. We used harvested olive tree prunings, melaleuca and wattle. Having done the Artful LFA exercise, we were primed to understand how the brush packs will protect exposed areas of ground, slow water flows, hold moisture and create microclimates that provide refuge and habitat for critters. As rainfall brings leaf litter and sediment down the slope, it will be caught by the brush pack, building up soil and fertility on that spot.

Photos by Alex Wisser

We returned to camp, in the damp, and started a fire. While dinner was cooking (thanks Alice Wood!!) we were treated to something very special: a language lesson with Wiradjuri cultural educators Emma Syme and Josie McConnell. We spoke and sang a variety of words about the landscape, animals and culture of Wiradjuri Country. Emma and Josie arranged us in a long line of pairs, exchanging warm greetings, our voices and giggles ringing in the twilight. A Wiradjuri rendition of ‘we are Australian’ was also sung. Emma and Josie brought their irrepressible warmth and cheeky humour to the whole experience, they are extraordinary women.

Photos above by Alex Wisser (top and bottom) and Lucas Ihlein (middle).

The following day we packed off to Canobales Farm, the property of KSCA’s Leanne Thompson and her husband Paul. Leanne’s brand new art studio, which will soon host workshops of all kinds, was filled with lively craftful activity. There were three unique stations:

A meditative Dorodango Ball activity with local potter Anne Smith. Anne dreamt up this activity to immerse us in a tactile encounter with local terracotta clays. A true free spirit, she shared stories of her life as a potter and former Lithgow school teacher, and her adventures living in the Valley.

A weaving project with Leanne Thompson, who has a unique talent for dreaming up imaginative sculptural projects that can also heal the land. In this case we were making a phragmites nursery in her dam. As we explored in the first Land Studio (and see this video), phragmites australis are a native reed species that used to be widespread in the Valley’s wetlands. From Leanne’s collection of natural materials, we made nests and vessels of all kinds that were ultimately strung across the dam, with phragmites plants submerged within.

A clay modelling exercise, stewarded by local catchment model maker Gary McQuigan and Laura. You wouldn’t know it as he’s a humble sort, but Gary is in demand from councils and museums around the country for his highly detailed, interactive, educational, to-scale models of rural and urban catchments. Laura (who now works at The Mulloon Institute) had invited him to co-deliver this citizen science workshop, to model three versions of a degraded Capertee valley floodplain pocket, drawing on satellite imagery of the site. Using white and terracotta clay, Gary’s wonderful tools, natural materials and blue food dye, we crafted the landscape as it may have been before European agriculture, as it is now, and as it could be in the future, focusing in particular on how water would move through it. This activity was testing model-making as a vehicle for understanding the science of the water cycle, catchment health and landscape rehydration.

Photos by Alex Wisser

Photos by Lucas Ihlein (top) and Laura Fisher (bottom).

But the day was not yet over! We then headed to the Glen Davis common. This is a neglected riverside site that used to be grazed and is now heavily overgrown with weeds. In the poster to the right, it is the curvy green shape in the top half of the image. This remarkable artefact dated 1940 shows the layout of the township designed to house the workforce for the Glen Davis Oil Shale Works, which at one point was 2000 people.

Capertee Valley Landcare has a new arrangement with Lithgow Council to regenerate the native ecology of the Common and make it accessible to the community for gatherings and recreation. We were excited to join Capertee Valley Landcare members and participate in a Water Ceremony with Peter Swain to mark this milestone. We took off our shoes, settled our minds, and reflecting on what healing Country can look like and feel like, on this little patch of ground. This was one of a string of water ceremonies that Peter has led across the Valley, in which stones warmed by the fire and many hands are placed in the river as talismans of connection and intention. They have drawn hundreds of people into intimate, memorable relation with Valley waterways and landscapes.

Photo at top right by Amelie Vanderstock, all others by Alex Wisser.

We settled around the campfire again that evening, knackered but very cheery. We were entertained with music, stories and poetry from within the group, including a poem Will Druce wrote that day, which you can read here. Don Poo Leone’s avatar Lucas Ihlein took advantage of the moment to launch volume 1 and volume 2 of the zine Glimpses of Pootopia, ‘a new publication to gather stories about experiments - in the suburbs, in the bush, in cities - in treating HUMAN MANURE as a valuable resource….’ and we poo-punned our way to bedtime.

Photos by Lucas Ihlein

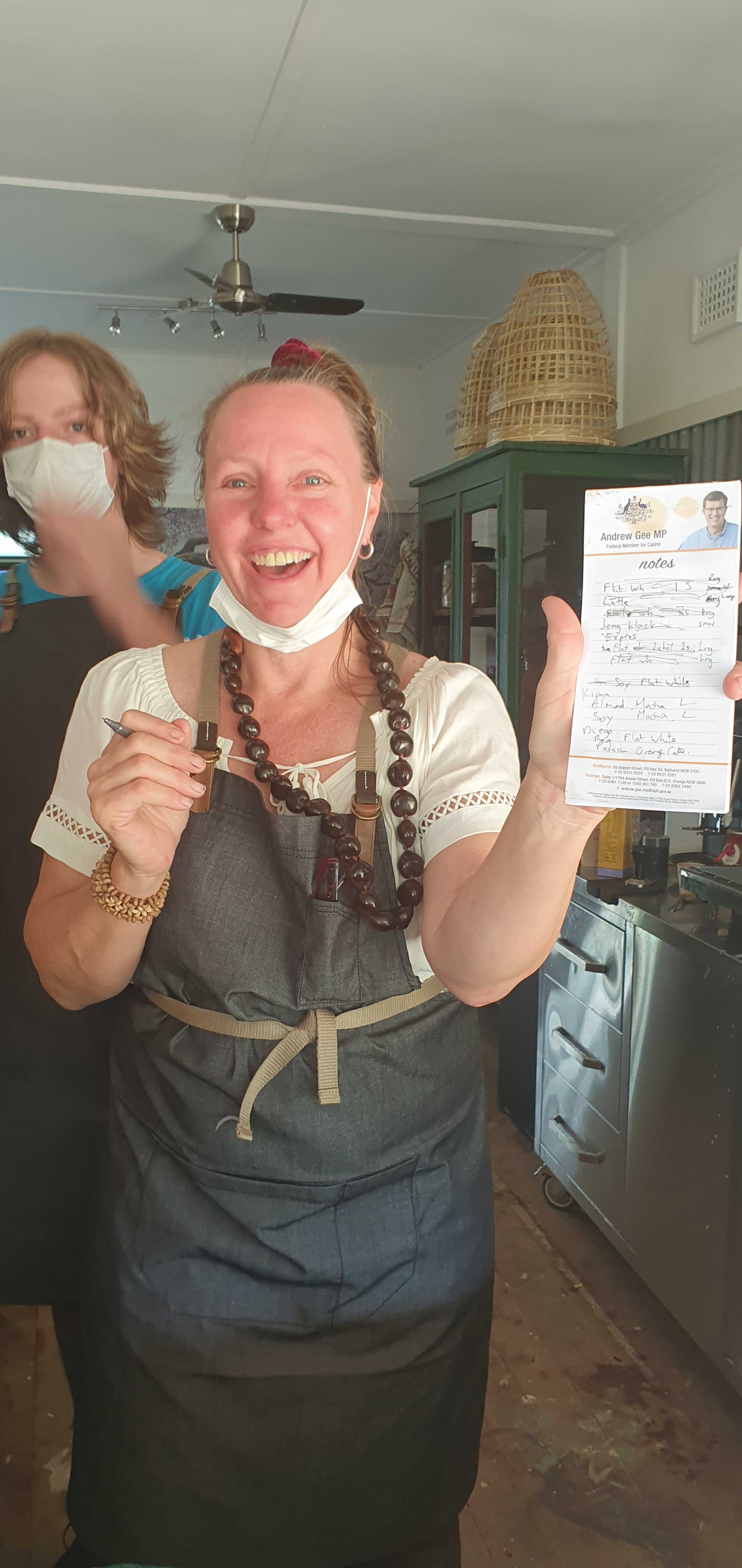

The sun came up for a steamy pack-down the following morning. We thanked the Dawsons for their always gracious hospitality, delivered our waste to Canobales Farm where it will do good, and concluded our gathering with a coffee at From the Paddock, Capertee’s brand new produce shop and cafe. It’s the project of Terri Wallace, the farmer who hosted the first Land Studio pin weir workshop at her property. Definitely worth a visit when you head to the Valley and if you’re lucky you’ll catch a chat with Kerrie Cook.

Land Studio is a big and kind of improvised effort of coordination, and I, Laura, extend huge gratitude to Lucas Ihlein and Kim Williams for being trojan fellow adventurers on that coordination journey. Thanks also to various Land Studio participants who put in some solid time to helping set up a campsite suitable to rainy conditions and helping with tasks on the fly, and all our hosts, artists and collaborators for giving us such a fantastic time.

This camp was part of the Land Studio Pilot Project, funded by the NSW Government’s Increased Resilience to Climate Change Community Grants Program. The video below was made for the Adapt NSW website, on which Land Studio features as a Case Study project. It was also supported by funding from the Federal Government funding through a Citizen Science grant.

See you next time!