By Georgie Pollard

It’s taken me a long time to write this blogpost. The Capertee Valley hydrology project was a big, complicated project with lots of threads. Within the project there was a lot of information but a lot of it was very practical, ways of seeing that could only be learnt by being there. The change in perception that we were all being taught was embedded in the landscape, through workshops. Through getting our hands dirty.

My role in the project was to make a map, and the map would be an artifact that would sum up the project. The process of learning about how to take care of the land differently would be represented in an image in relationship to the landscape. The Capertee Valley Hydrology project was initiated by Kerrie Cook, president of Capertee Valley Landcare. Kerrie’s idea was that social isolation and the effects of drought that farmers face can be addressed through hydrating the landscape together. When we are connected to land and each other we are better equipped to adapt to the significant disruptions to life that will come with climate change. Water is the common thread that connects droughts, fire, floods, plants, livestock, and people. Water is the element of the landscape that could connect and heal a community, at the same time as healing the land.

The Capertee Valley Hydrology project was full of great workshops. Natural Sequence Farming, Hydrology, Salinity, Weeds and Weaving. All of the workshops were different ways of perceiving the land, and understanding that our perception of the land has consequences. We are all aware of how seeing the land through an English lens has shaped our farming methods for the last 200 years and we know that this isn’t working, and we’ve known it for a long time now. Playing with perception is just one of those things that art excels at. It’s from this perspective that it’s easy to see Natural Sequence Farming as “art”. To look at the landscape through the lens of hydrology, salinity or the benefits of weeds will inevitably change how we look after it.

We can’t talk about our relationship to the landscape without talking about colonisation and the ways in which the original inhabitants of this land took care of it. To help us on this journey we spent time with Peter Swain. Born on Dabee land, Peter is a descendant of Jim and Peggy Lambert, survivors of the Dabee tribe who were massacred on this land 198 years ago. Peter was an invaluable part of this whole project, he changed my perception of what we were doing and helped me conceive of how to include the history of this area on the map. 40,000 years of practice that stopped 198 years ago. While the knowledge lives on, its accumulation over 1,600 generations was discarded. Peter took us on walks in different parts of the valley. He has a truly impressive ability to read the landscape over time. On one walk, we would have been around 800 metres above sea level when he and Jo Albany found a scar tree, a tree that would have been used to make a canoe hundreds of years ago. Meaning that we were standing in the hills where water once flowed.

Peter Swain is also one of the people Stephen Gapps spoke to as he was writing the book “Gudyarra- the first wiradyuri war of resistance”. The book Gudyarra is a map. It follows the building of the roads over the blue mountains and into the plains out to Bathurst, Mudgee, Olinda and here in the Capertee. It records the war that came with the maps and the roads. The old maps describe it in a few black lines on white paper. If you created a flip book of all those old 19th century maps over time they would reveal the course of colonisation. And these maps look innocent, they are just lines on paper right? Gudyarra reminds us that those lines were never innocent. It details warriors, deaths, revenge, humiliation, the bits that the black lines don’t mention.

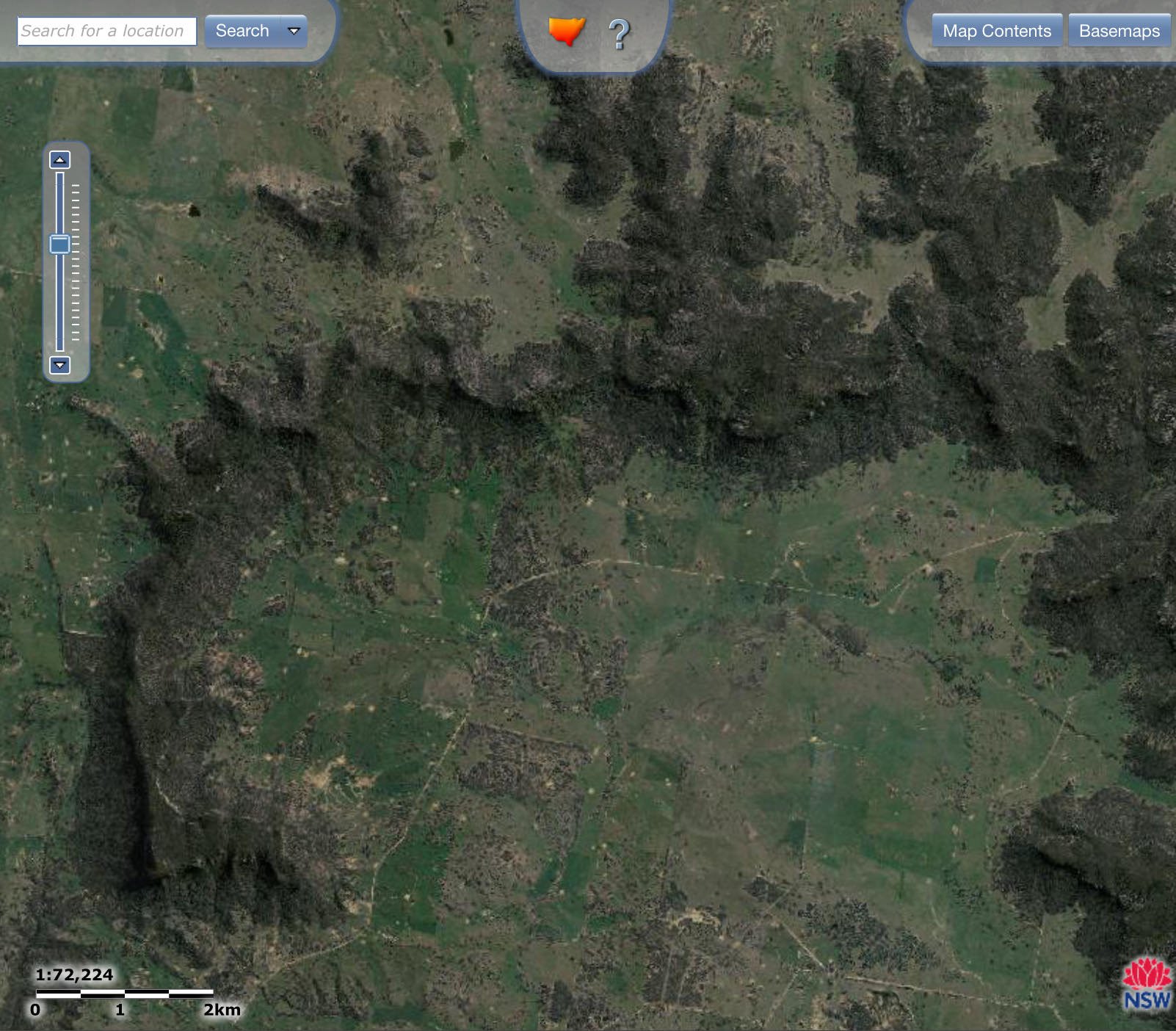

The black lines don’t mention a lot of things. All maps are an interpretation. But just like a good story, or a legible map, this blogpost necessarily has to leave a whole lot out. The reference I used to put this map together was sixmaps, which is a cadastral map. Put simply, cadastral maps are maps about property. They tell you what infrastructure is available to you but also what you can do with your property. A cadastral map will tell you what and where but it doesn’t tell you who, when and how (unless you know how to look). Maps can be about anything, but cadastral maps are particular in their “objectivity”. Emptying out not just the subjective elements of living in a place and replacing it with a sort of absent authority, they also exclude any contradictions or context that would destabilise the authority of a map.

The history of this place destabilises the authority of a cadastral map; there is a lot of power in “always was, always will be”. The objective power of cadastral maps comes from the what and the where. To look at a map we place ourselves; I’m here, next to this rock, and look, there it is on the map. Oh yes, we agree, that is a fact. And the relationship that rock has to the river or to the road becomes “natural”. And the authority of the map becomes “truth”, as if truths were naked, innocent (to read more about this go here). I have an image of the cartographer, drawing the map and if questioned about their interpretation of the land, the cartographer throws up their hands and says “I’m just drawing what’s there, i have nothing to do with it”. Facts relieve us of our relationship to the land, our responsibility to it.

Facts are never naked. Our relationship to the land, that rock, is specified, mediated through the map. Your relationship to that rock is regulated. To look up at that rock now, every centimetre of that wild bush land up there is legislated, regulated, licensed, titled, monetised. It’s not objective, it's culture. That is the culture that replaced Aboriginal culture here in the Capertee Valley 198 years ago. Objectivity does a lot of work backstage while it proclaims innocence.

This map of the capertee valley is a collage, made from cut up seed catalogues and painted in watercolours. The words refer to plants and their uses, growth habits and price per kilo. There are authors and book titles, references to composting and biodynamic farming, Rudolf Steiner and spiritual relationships to land. They are placed so as to resemble weaving, referencing the workshops conducted by Leanne Thompson, Peter Williamson and Lani Mackenzie. The weaving element of this project was highly successful. It brought people together after the fires and covid. Reeds and branches which are gifts from the land, were reconfigured in patterns and shapes, and were gifted back to the land along its contours.

Another element I loved about the Capertee Valley Hydrology Project and all of its workshops is the “how”. The many different types of “how”. A map doesn’t tell you how to look after the landscape. But a diagram can. And that is what I’ve included around the outside of the map in blues and greens. It’s a diagram of Natural Sequence Farming. On one side we see the water flowing, draining straight out of the valley and on the other side the vegetation and the chain of ponds that slows the water down.

A Diagram includes the “how” but it also includes time. Grief knows a type of time that is spatial. It knows the ever-present places you can’t return to anymore. Where the black and white maps of the 19th Century don’t include the history of the black and white war that took place here, I have included it in the map in red. I’ve also included the draining of the valley that happened as ecosystems were destroyed and the rivers and creeks were incised, so that the water would flow out of the valley.

In conclusion, we can’t have a relationship to that rock that is unmediated. That rock will kill you. Without language, without clothes, rope, supplies or without friends that care where you are, that rock will kill you. So from here, we can’t go unmediated, and that is what this map that I have made is about. It’s an attempt at looking at the landscape, mediated through remembering who we are, our history and our relationship to Aboriginal culture. I hope it is a mnemonic device: Remember those workshops? Remember that time we came together to refocus our attention back to looking after the land?