The Capertee Hydrology Project wove it's way through the Valley and its community in so many ways, highlighting the importance of slow-moving water for resilient landscapes. Leanne Thompson tells the story.

Capertee Weaving and the Water Ceremony

By Alex Wisser

On the 14th of November, a handful of Capertee residents, myself and fellow travellers on the Capertee Weaving Water Project woke at four in the morning and travelled to the top of Dunville Loop in The Capertee Valley. We were met by traditional custodian Peter Swain and several of his family, and drove in procession along the base of the escarpment to a stream crossing the road where we parked and gathered in a circle. Ochre was passed around as Peter worked to get the fire going in the Coolamon. This was our first attempt at a water ceremony along the Capertee River. Despite a good bit of early morning confusion, it began at the moment of sunrise, as planned. The sun crested the cliffs to the North, somewhere above the source of the small tributary that flowed across the road as Peter smoked the circle of people gathered and spoke to us of what we were doing here, on this road at this river in this valley.

The Water Ceremony, he explained, was originally performed as a collective expression of the various clans that lived along a water course. They would meet at its source, as we were doing, and throughout the Ceremonial Season, the ceremony would be performed along the river. As the water moved from country to country, the ceremony was reperformed, acknowledging the connection that water made between the peoples that lived along its course, that shared the life it distributed across Nation boundaries. This was continued until the river reached the sea. This ceremony would only last one day. As it was the first attempt, it had been decided that we would start small, with the idea that it could be repeated in following years with other clans invited to participate.

A large quartz stone was found and the ceremony began. The stone was smoked, and then passed around the circle. As each of us held the stone, we were asked to put into it the energy of that which we wished to contribute to the river: a wish, a desire, a hope, a feeling: whatever we would like to send down the river. After the stone had been passed around the circle, it was lowered into the river where the energy that we had invested in it would be carried away by the flowing water.

This might not sound like a particularly challenging thing to do, but it was also not a simple act. I cannot say how anyone else in the circle felt about what we were doing, but for me, inside the privacy of my own thoughts, there were voices that niggled at the earnestness of what we were doing. What right did I have to be here? Wasn’t this some kind of childish pretending? To put my doubts into words is to formulate them as something more definite than they were but there they were, swirling around in my head as usual, undercutting the world around me with their protective shield of skepticism. Peter had explained that painting with ochre allowed the ancestors to see you, and so, this kind of self-consciousness was understandable. I let these thoughts do their bit, being old enough to know that they are easily exhausted by their own energy. The sincerity of what we were doing was enough for me to put aside my reservations and quietly participate. Into the stone I put not a wish or a desire, and not a hope or a single word of intention, but instead I gave to it only the silence that I had in me. The river did not want me to tell it what I thought. I knew this much.

We were also invited to select individual stones that we could put our personal thoughts into and we quietly dropped these into the stream. We repeated the ceremony several times, stopping at two other spots along the river before gathering at Glenn Alice Hall for lunch. Here we were met by a much larger group of people who ate with us and the ceremony was once again repeated. The stone was again passed around and smoked and then lowered into the river by another member of the group.

We continued down the valley, stopping next at The Capertee Water Weaving project, a rambling 21 metre long artwork of woven organic material that traced the contour of a small hillside, made by the Capertee community under the guidance of lead artist Leanne Thompson. The work, as with the ceremony, is part of our larger project to generate a community wide consideration of the hydrology of the valley, integrating cultural interventions like these ones with the delivery of workshops in Natural Sequence Farming techniques and a scientific understanding of the hydrology of the valley. The rambling structure of wicker circles, bound together into a crazy fence on the hillside in the middle of the valley had about it an irrepressible energy. It is rare that a community engaged artwork is able to carry the kind of spontaneity and life that this work projected.

Again we moved down the valley, and arrived at our final station, at Coorongooba, where Coorongooba creek met the Capertee River. From here it continued through the mountains to become the Colo River before joining the Hawkesbury on the Eastern Plains and from there flowing out to the sea. A spot had been chosen and a tree selected. A carving was made into the tree, in a design based on the meeting of the two waters at Coorongooba. The audience was invited to apply ochre to the design. We performed another ceremony, circling the tree in a gesture of gratitude.

A final water ceremony was performed at the meeting of the two waters, at sunset, completing the cycle. The day was finished off around the fire at the campsite above the river.

Thinking back over the day, I found it to be an odd combination of cultures. In contrast to the reverence of the ceremony, the artwork stood as an exuberant celebration on the hillside. The meaning of the various parts of this day seemed to balance in contrast to one another. The performance of an ancient ceremony and the construction of a completely new-born thing. Against the backdrop of the valley, the two can be brought together as the spectrum of culture. The one was the opportunity, so rare in our modern experience, to pay respect to the world of which we are a part, and the other was our capacity, as a part of that world, as a participant of that landscape, to produce life, to express its joyful fleeting energy, its effulgence and fecundity. The artwork participated in the life of the grass and the expression of the wild flowers that surrounded it, as the ceremony participated in the silent weighted and impenetrable persistence of rocks over which water flows to the sea.

This project was made possible through funding support from the above

Land Studio in the Capertee Valley

Fire Without Smoke - The Story of Biochar

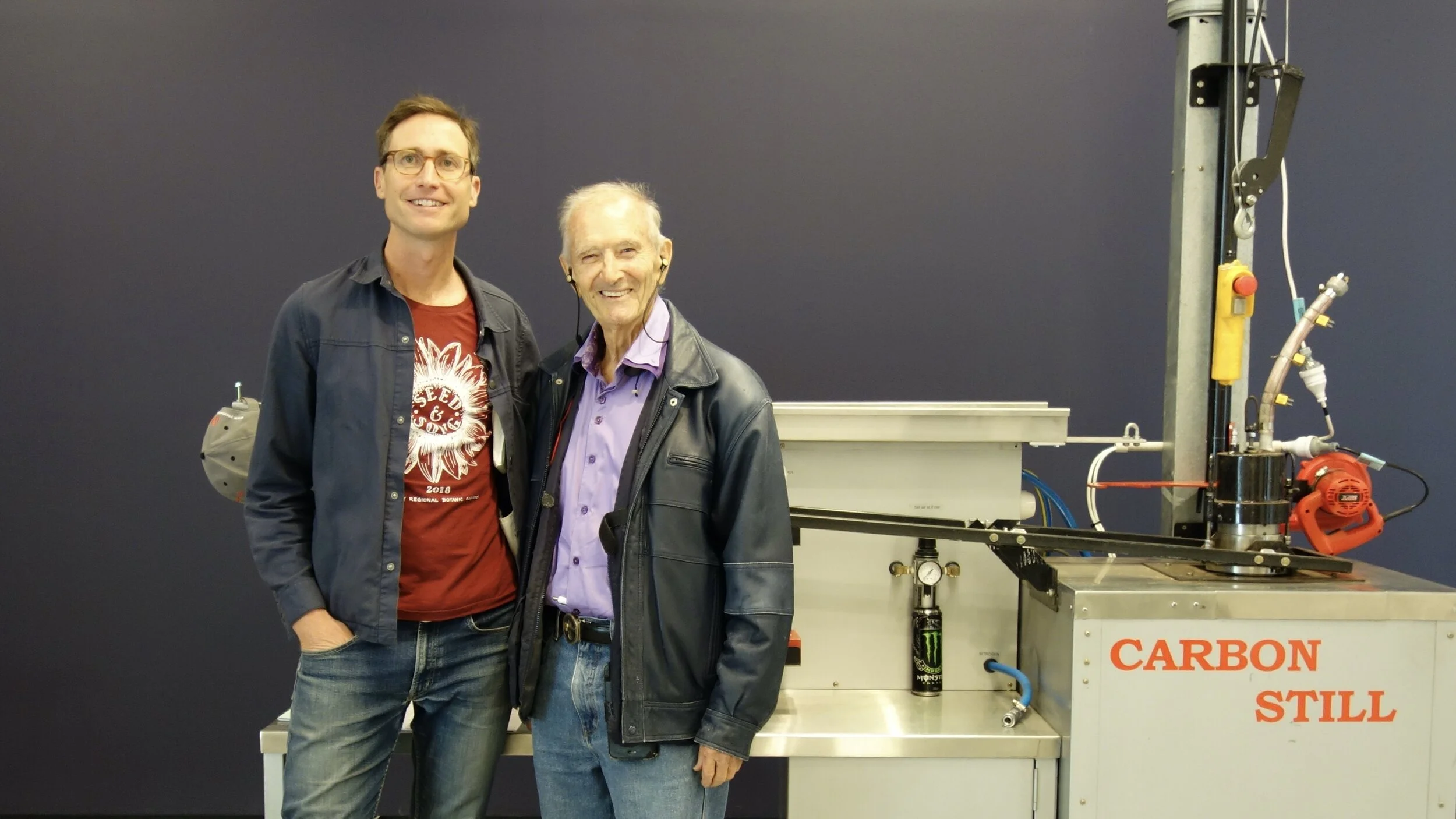

Another instalment of the adventure otherwise known as “An Artist, a Farmer, and a Scientist Walk into a Bar…”. In this video artist Georgina Pollard takes us through the physical and cultural properties of Pyrolysis, the engagement of carbon in art, charcoal and the soil. Scientist Ruy Anaya de la Rosa and social change agent, Adam Blakester talk about their international project, Biochar for Sustainable Soils disseminating biochar process to farmers around the globe. They also talk about the benefits of working with artists to create the cultural change that needs to back the technological changes they are promoting.

The art of soil carbon sequestration

The Earth You Cannot Know

Alex Wisser takes you on a journey into the earth. In his own words, it was a journey that progressed at a rate of several centimetres per day, as he made his way into the ground, hand digging a three metre deep hole that took him through an involved contemplation of the meaning of the earth and the many facets of our relationship to it.

Videography by Justin Hewitson.

This project was supported by 'An artist, a farmer & a scientist walk into a bar…' a major arts initiative in rural Australia in 2018-2020. Involving 9 artists, it was a series of collaborations exploring regenerative farming, soil health, Aboriginal country, solar energy, carbon sequestration and wild foods. It was led by Kandos School of Cultural Adaptation (KSCA), working in partnership with Cementa Inc., The Living Classroom and Starfish Initiatives, and was funded by the NSW Government through Create NSW. You can find out more at https://www.ksca.land/alex-wisser-project

Weaving Water Workshop June 2020

The Story of the WildFood Store

humus:human - the video

Farmers in Flux

It’s funny how time gets away from you. This year I took the big leap to study full-time Honours in Ecology at UNE, and while I am loving every minute of it, my brain is too full of measuring pasture groundcover and landscape function to make space for anything else. And so, despite my best intentions I am yet to publish my farmer stories for ‘Farmers in Flux’.